Shiva and the Trinity of Existence

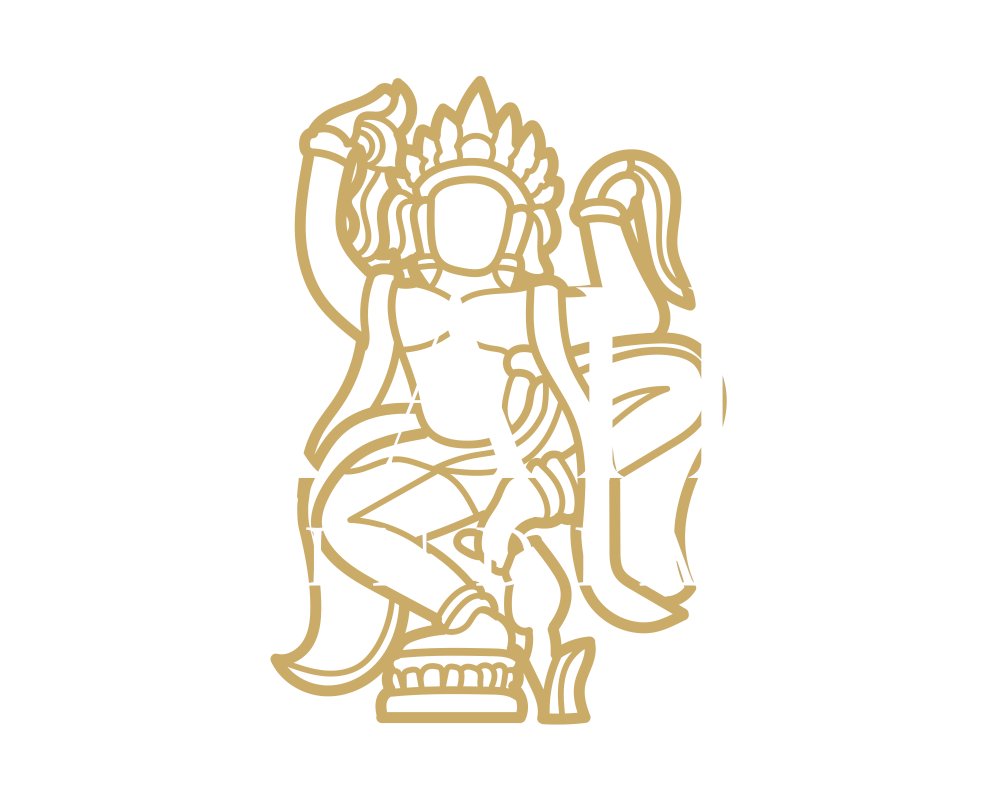

Brahm's inaugural post: the Shiva Trimurti, a small sculpture with vast meaning.

SUMMARY

The Shiva Trimurti of Mamallapuram is more than a sculpture — it’s a meditation on existence. Three faces hold creation, continuity, and change in perfect balance, a rhythm echoed across cultures from Egypt to Greece to Christianity. Small in scale yet vast in meaning, this hand-carved piece invites us to see life not as linear, but as a cycle — where every ending carries the seed of a beginning.

At first glance, the Shiva Trimurti appears to be a sculpture of divine calm. But look closer, and it becomes a map of the human condition, carved not in metaphor, but in stone.

Close up of the Stone Shiva Trimurti

"We begin this blog with the Shiva Trimurti because it offers not a fixed idea, but a frame for reflection."

The Shiva Trimurti and the Universal Pattern of Threes

This piece from Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, carved from stone in the traditional South Indian idiom, shows three seamlessly joined faces - a configuration known as Trimurti, or “three forms.”

It represents:

- Brahma the Creator

- Vishnu the Preserver

- Shiva the Destroyer

the divine cycle of creation, preservation, and dissolution at the heart of Hindu cosmology.

But this triadic form is not unique to India. It appears across cultures and centuries, a shared human intuition about the rhythm of existence:

- In Egypt: Amun, Re, Ptah

- In Persia: Ahura Mazda, Mithra, Anahita

- In Rome: Diana Triformis - goddess of the moon, the hunt, and the underworld

- In Greece: Hecate, invoked in magical papyri as “triple-headed, triple-voiced”

- In Ireland: The Morrígan, the triple goddess of battle and fate

- In Northwestern Europe: The Matres, triple mother goddesses of fertility and protection

- In Christianity: Father, Son, Holy Spirit

The Archetype of Three

Carl Jung identified this cross-cultural pattern as an archetype—what he called “triadic completeness.” In mythology and art, three signals movement: beginning, middle, end. In philosophy: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. In nature: a triangle—the simplest stable shape. In consciousness: past, present, future.

This Shiva sculpture encapsulates that logic.

- One face leans toward the past: the force of creation.

- One steadies forward: the burden of continuity.

- And the third turns away: the inevitability of change.

The reverse of the Shiva sculpture features a serpentine motif, symbol of kundalini energy, often interpreted as the uncoiling force of spiritual awakening. This is not decorative—it completes the sculpture’s architecture: from myth to philosophy, from symbol to energy.

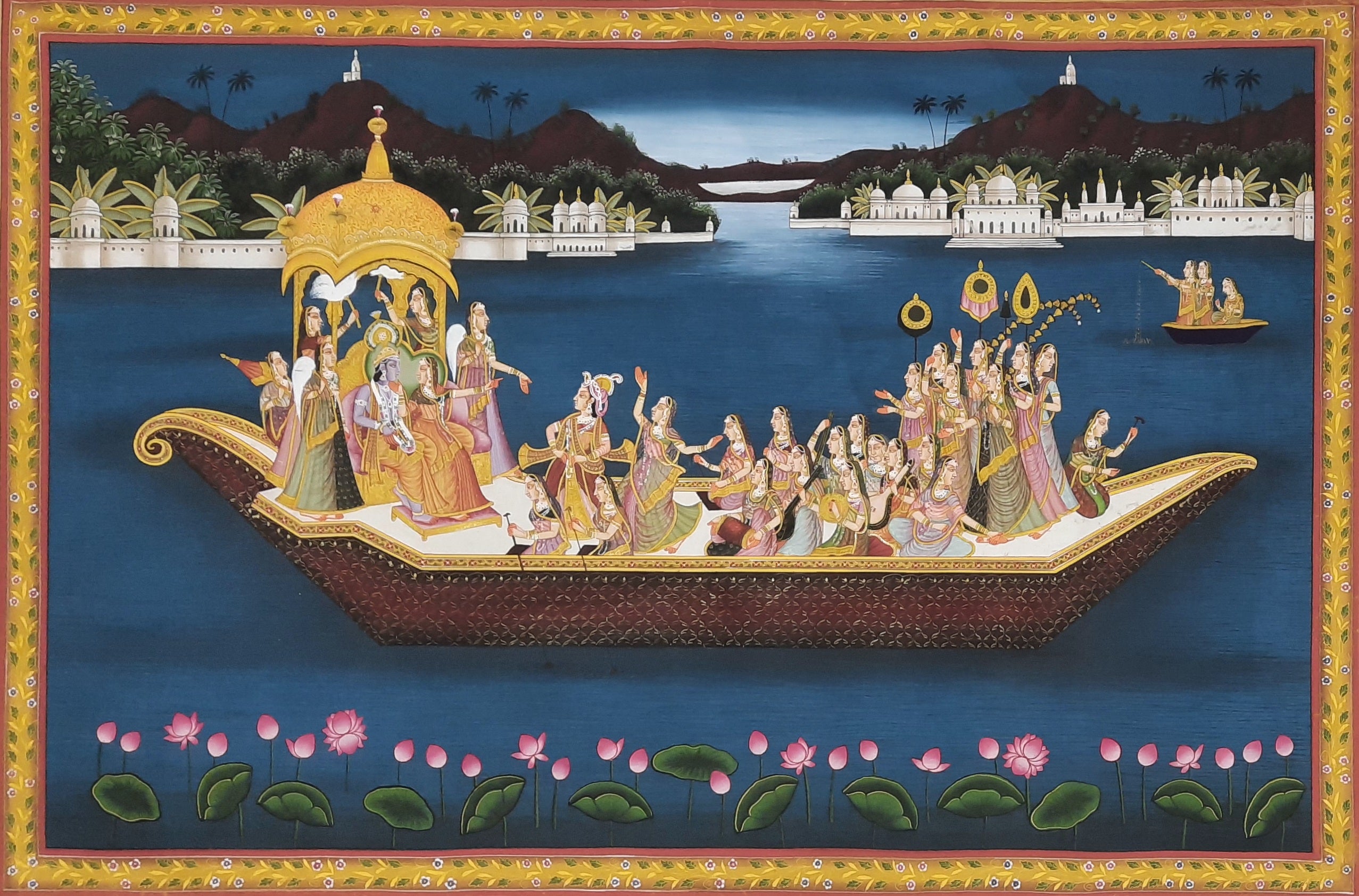

Unlike in Western conceptions of linear time, the Trimurti offers a cyclical worldview. There is no final triumph, no end state. Each phase gives way to the next. This worldview shaped not just theology but city planning, temple architecture, and artistic tradition across India and the wider Indo-European world.

From Platonic triads in Greek philosophy (Zeus, Poseidon, Hades), to the trifunctional hypothesis of Georges Dumézil (sovereignty, force, fertility), the triad is a deep structure in how human beings have ordered their understanding of the cosmos.

The Shiva sculpture you see here - 16 cm tall, 1kg in weight - is small in scale but vast in scope. It is hand-carved by master artisans and stands as both a spiritual object and a cultural artefact. Its aesthetic - graceful yet geometric, with interlocking forms and balanced symmetry - makes it as architectural as it is devotional.

We begin this blog with the Shiva Trimurti because it offers not a fixed idea, but a frame for reflection. Not a doctrine, but a rhythm.

Creation. Continuity. Change.

That is the Trinity of Existence.

The video below takes us to Tamil Nadu, where a 112-foot steel bust of Shiva was designed and built by hundreds of volunteers. The piece was created to embody stillness, intoxication, and exuberance all on a single face — qualities that define Shiva in his cosmic role. It’s a modern work, yet its scale and intent mirror the spirit of the Trimurti: to turn stone and metal into a meditation on human existence.

What does the Shiva Trimurti represent?

The Shiva Trimurti unites Brahma (creation), Vishnu (preservation), and Shiva (destruction) into one form — a reminder that existence moves in cycles, not straight lines.

What is special about the Shiva piece featured here?

This sculpture is 16 cm tall and weighs 1 kg, but its small scale belies its significance. Hand-carved by master artisans in Mamallapuram — a UNESCO World Heritage site known for its Pallava-era stone carving tradition — the piece carries forward a craft lineage that is over a thousand years old. Its three seamlessly joined faces achieve a rare balance of geometry and grace, making it feel almost architectural despite its size. The reverse side features a finely carved serpentine motif, a symbol of kundalini energy and spiritual awakening, which completes the sculpture’s philosophical and aesthetic design. Each piece is made individually, with visible tool marks that signal the presence of the artisan’s hand, giving it a unique character.

Can I purchase this sculpture from BRAHM?

Yes — we offer a single, hand-carved Shiva Trimurti sculpture. We ship internationally with secure packaging and authenticity guarantees.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.